Alfa Romeo 16C Bimotore: the Beast!

- COCKPIT

- Dec 11, 2021

- 5 min read

In the mid-1930s, Grand Prix racing was tirelessly dominated by German cars: Auto Union and Mercedes. This show of force by Nazi Germany is not to the taste of a certain Benito Mussolini who demands an Italian response. Enzo Ferrari, then sports director of Alfa Romeo, then thinks of a P3, the racing car of the time, but doped by ... a second engine at the rear!

An uncontrollable monster

In just four months, the car was finished. It is made up of two 8-cylinder in-line engines, together developing well over 500 horsepower! With such power, Enzo Ferrari thinks he can beat the Mercedes.

In 1933, Alfa Romeo, which never had much luck in balancing its books, decided to temporarily withdraw from racing to concentrate mainly on the production of road cars, leaving its Alfa Corse racing program to nil. other than Enzo Ferrari himself, under the name of his own Scuderia Ferrari. Its main task was to contain the dizzying ascent of the technically superior German teams, Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, who were performing their powerful W25 and Type B on newly cobbled Reichsautobahnen, and setting a series of ground speed records in the process. . This would mark the start of another great rivalry in motorsport history, between Le Rosse and the Flèches d'Argent, which will last to the present day, extending beyond the track, to include the foundry. and the chemistry lab.

Thanks to their ability to create new, lighter composite metals, the Germans were able to radically increase the displacement of their engines (more than 4000 cm3) while keeping a total weight lower than that of the previous materials. This created a real challenge for Alfa Romeo, which had hitherto enjoyed great success with its nimble 2.6-liter Tipo B P3 cars. On top of that, Germany had secured an enviable roster of drivers, with Rudolf Caracciola, Manfred von Brauchitsch and Luigi Fagioli racing for Mercedes-Benz, and Hans Stuck, Achille Varzi and Bernd Rosemeyer for Auto Union.

In 1935, faced with this knowledge and the extreme pressure of the Italian regime to prove its power on the world stage during the next three Formula Libre events (on the new high-speed circuits of Tunis, Tripoli and Berlin), Enzo Ferrari had to think fast and, above all, think outside the box. None of the existing Alfas had the strength to face this type of super-fast test. A new car had to be built. And despite having two great drivers in the team (René Dreyfus from France and Louis Chiron from Monaco), Ferrari knew deep down that only one driver could meet this challenge. His name was Tazio Giorgio Nuvolari. In Italy, it is still called “Il Mantovano Volante”.

One of the most proficient racers in history and the inventor (or discoverer) of the drift turn, Tazio Nuvolari was racing for the Maserati team at the time. Some say it was Benito Mussolini himself who demanded he return to Alfa Romeo that year, but I like to think that it was mostly Enzo's promise of a bespoke race car. unprecedented that ultimately convinced him to return to the Scuderia.

The Bimotore in front of a Mercedes W25 at the 1935 Tripoli Grand Prix.

This image was important for the fascist regime: Tripoli being part of Italian Libya, an Alfa in front of a German Mercedes was a perfect propaganda tool.

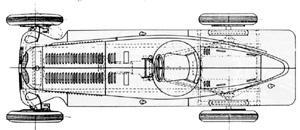

And it was a truly unprecedented car. Weighing 1,300 kilos, the 16C Bimotore was fitted with two supercharged inline-8 Alfa Romeo engines ("16C" for the number of cylinders), one at the front of the car and one just behind the cockpit, carrying the displacement total to a whopping 6.3 liters and endowing the beast with 540 horsepower, overtaking both Mercedes and Auto Union cars (at 430 and 375 hp respectively.) Some call it the very first full-fledged Ferrari racing car.

Now for the bad news. You don't have to be an engineer to understand that adding a full second engine meant twice the volume of a single-engine car. And even more important than the actual weight of the race car is how that weight is distributed. On its first test on April 10, 1935, it was already clear that the power and top speed of the Bimotore (over 190 mph) came at a very high cost in terms of handling, tires and fuel economy. . Despite these concerns, there simply was no time to redesign the entire car in time for the three races the car was designed for.

At the Tunis Grand Prix, last minute tire problems during practice forced Nuvolari to leave his Bimotore to the pit and race on an obsolete P3, which had come out after a few laps and did not finish the race. A week later, at the Tripoli Grand Prix, the two Bimotore Nuvolari and Chiron only managed to finish fourth and fifth respectively behind the German teams. And finally, two weeks later at the Avusrennen in Berlin, only Luis Chiron conquered second place after Nuvolari failed to qualify for the final round of the race, again because of the Bimotore which was shredding without release his tires. Che disaster!

But maybe not a complete disaster after all. Before removing the car, Nuvolari set two land speed records on the Florence-Lucca highway on June 15, 1935, recording the flying kilometer at 11.2 seconds and the mile at 17.9 seconds, becoming the first to cross the 200 mph barrier. Its top speed on the second run exceeded 362 kilometers per hour, which is remarkable even by modern standards. But even without that silver lining, the 16C Bimotore could already be called a success as it represents Nuvolari's return to the Scuderia. More importantly, the car is a testament to that reckless inventiveness that drives motorsports, that willingness to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges by fully engaging even in the craziest flight of the imagination.

Retirement

This is enough for the pilots who must demonstrate extraordinary skill to handle this overpowering machine. Tazio Nuvolari tells the management of the brand that he prefers to drive the old car, which is much less powerful, but much more agile. It was good for him, because that was how he won the next Grand Prix, in Germany, moreover.

Record

The car is therefore stored. However, Alfa Romeo decides to make an impression with this vehicle. With Nuvolari at the wheel, the 16C Bimotore was therefore entitled to a last stand: the speed record for the kilometer launched, at a speed of 321 km / h and for the mile launched, at a speed of 323 km / h! The next day, the cars were stored in the factory and will never leave it ...

But the two-engine Alfa will never win. His only feat of arms will be a new speed record on the kilometer launched, set at 312 km / h by driver Tazio Nuvolari.

Comments